Kayapo: Background

The Xingu River, a major tributary of the Amazon in Brazil, begins in the semi-deciduous forests and woodland-savannas of Mato Grosso state and flows north for 2,700 km across varying topography before ending in the wet forests of the Amazon near Belem. The Xingu spans major tropical biomes from savanna (cerrado) in the headwaters of the south to semi-deciduous and evergreen wet canopy forests of the southern, mid- and northern regions. More than 20 linguistically differentiated indigenous cultures that hold millennia’s worth of ecological knowledge are found in the forests of the Xingu.

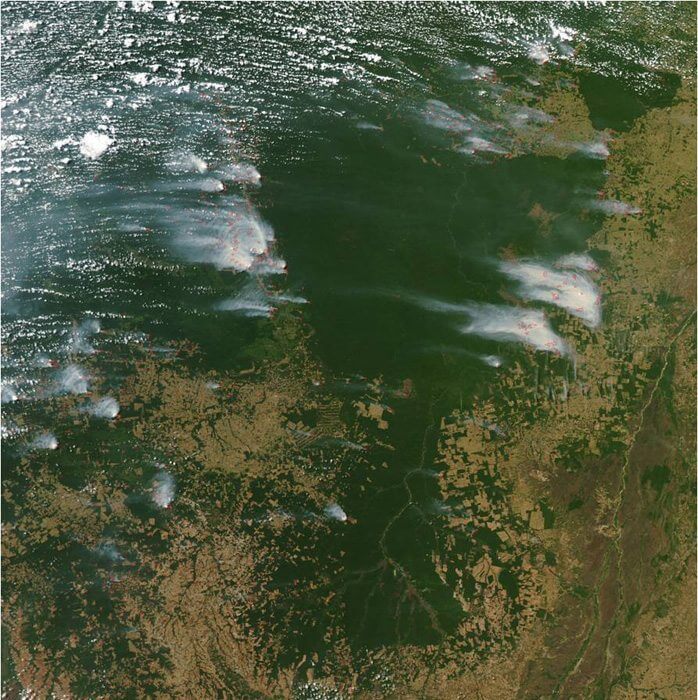

During the last four decades, the Xingu has been subject to increasingly intense deforestation as the agricultural frontier inexorably expands north and west. An “arc of fire” constituting the highest rate of deforestation in Brazil and indeed, one of the highest in the world, sweeps across the region. This process of colonization and agricultural expansion, often accompanied by violent land conflict in the lawless frontier, follows road construction, especially the perimetral framework of national highways.

With adequate roads and suitable soils, the Xingu has become an important centre for cattle production (occupying the greatest tracts of land and by far the greatest driver of deforestation), logging (almost all illegal) and production of soy bean for export. Dozens of towns have sprung up along roads to support frontier activities and hundreds of thousands of people depend on the frontier economy.

While this tsunami of forest destruction threatens to engulf the region, an enormous 28.8-million-ha network of protected areas (including both ratified indigenous territories and conservation areas) secures protection in law of 56% of the Xingu basin. This protected areas corridor is the great hope for conservation of multi-landscape scale tracts of southeastern Amazonian forest with all its magnificent richness of biodiversity, indigenous cultures and ecosystem services. Indigenous lands of the Xingu are of particular importance because they occupy two thirds of the protected areas corridor and possess de facto protection services — their indigenous inhabitants. Over the past three decades, indigenous territories have proved formidable barriers to forest destruction.

Satellite image of Kayapo lands and most of the Xingu Indigenous Park (to the south) showing plumes of smoke rising from burning of primary forest remnants outside of the Indigenous Territories. Dark green areas are indigenous lands and light brown areas are ranch and agricultural land.

However, outside pressure on Kayapo lands continues to increase. If borders are not well monitored in this lawless region of weak governance; ranching, fraudulent land speculation, commercial fishing, logging and gold-mining inevitably invade and encroach into protected areas. If they cannot gain clandestine entry, loggers and goldminers will attempt to buy off Kayapo individuals to obtain access to the rich timber stocks and gold on their lands. Sometimes they are successful. Once a door is opened, it is hard for even the Kayapo to control an influx. When they lack information and sustainable economic alternatives, indigenous peoples are vulnerable to outside pressure to liquidate their resources.

Large infrastructure projects are an increasing threat to the region’s remaining forest: i.e., Kayapo land. The mining company Vale S/A operates a nickel mine near Tucuma. The mine has catalyzed immigration into the region increasing outside pressure on neighbouring Kayapo lands. At the same time, the third largest hydro dam in the world, “Belo Monte” is under construction on the Xingu river some 600km upriver from Kayapo lands in Para. To operate efficiently during the dry season, the turbines at Belo Monte will need water released from upriver holding dams –projected for building in Kayapo lands. In the west, the newly paved BR 163 highway from Cuiaba in the south to Santarem in the north has dramatically increased immigration into the region with associated pressure for illegal predatory resource extraction (logging, goldmining) and ranching on western Kayapo lands. Strengthening the capacity of Kayapo institutions to protect their boundaries, and develop sustainable income alternatives becomes even more crucial in the face of approaching large-scale industry.